THE NATURAL

A new show celebrates the work and life of folk artist Bill Traylor, with support from one of hisbiggest fans—Jerry Lauren

Jerry Lauren remembers clearly his introduction to the work of folk artist Bill Traylor some 25 years ago. Like many collectors, Lauren and his late wife, Susan, enjoyed combing the local antique auctions and art fairs near Colebrook, Connecticut, the Litchfield County town where they owned a 1785 weekend home. Gradually, the Laurens amassed an impressive collection of folk art—copper weather vanes, model trucks, stoneware jugs, and wooden duck decoys—that celebrated their love of Americana.

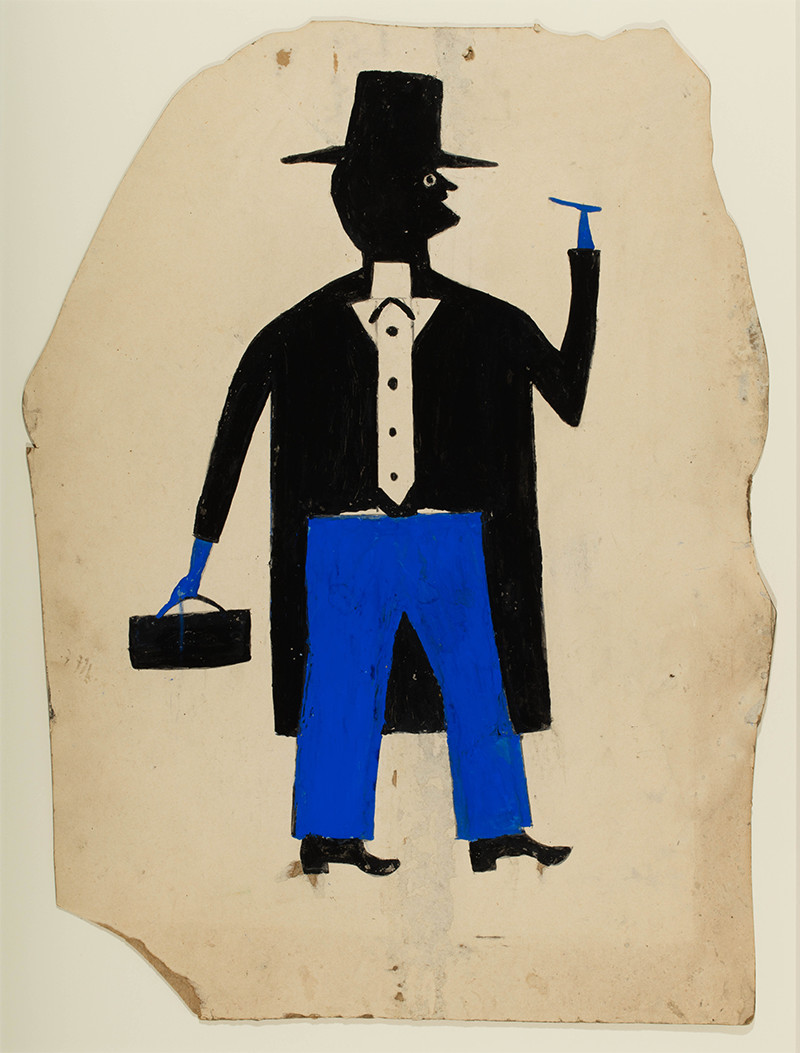

Then one day a trusted dealer showed them something new: a rudimentary painting on cardboard of a man wearing a green shirt and black top hat, holding a cane and smoking a cigar. Lauren was immediately intrigued by the anonymous strolling fellow—and even more so by the artist responsible. “Who is this person?” he asked.

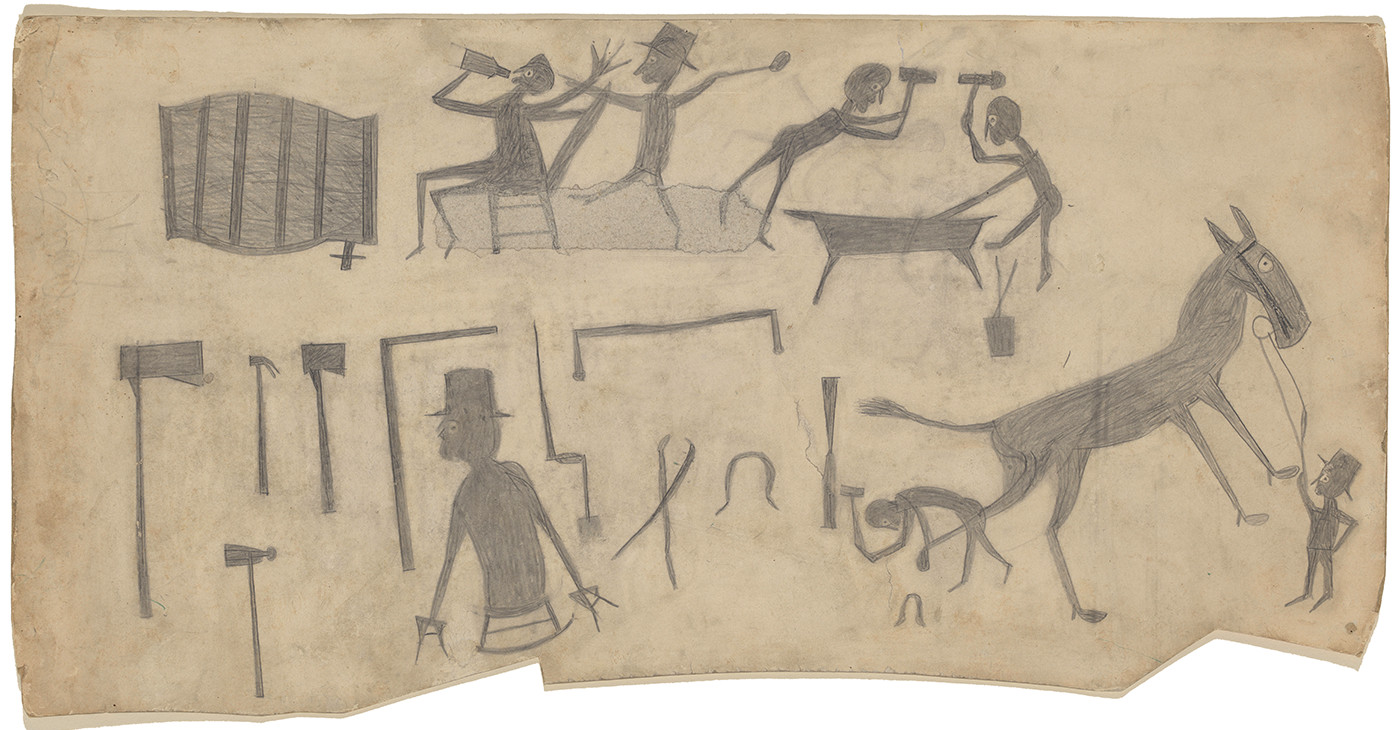

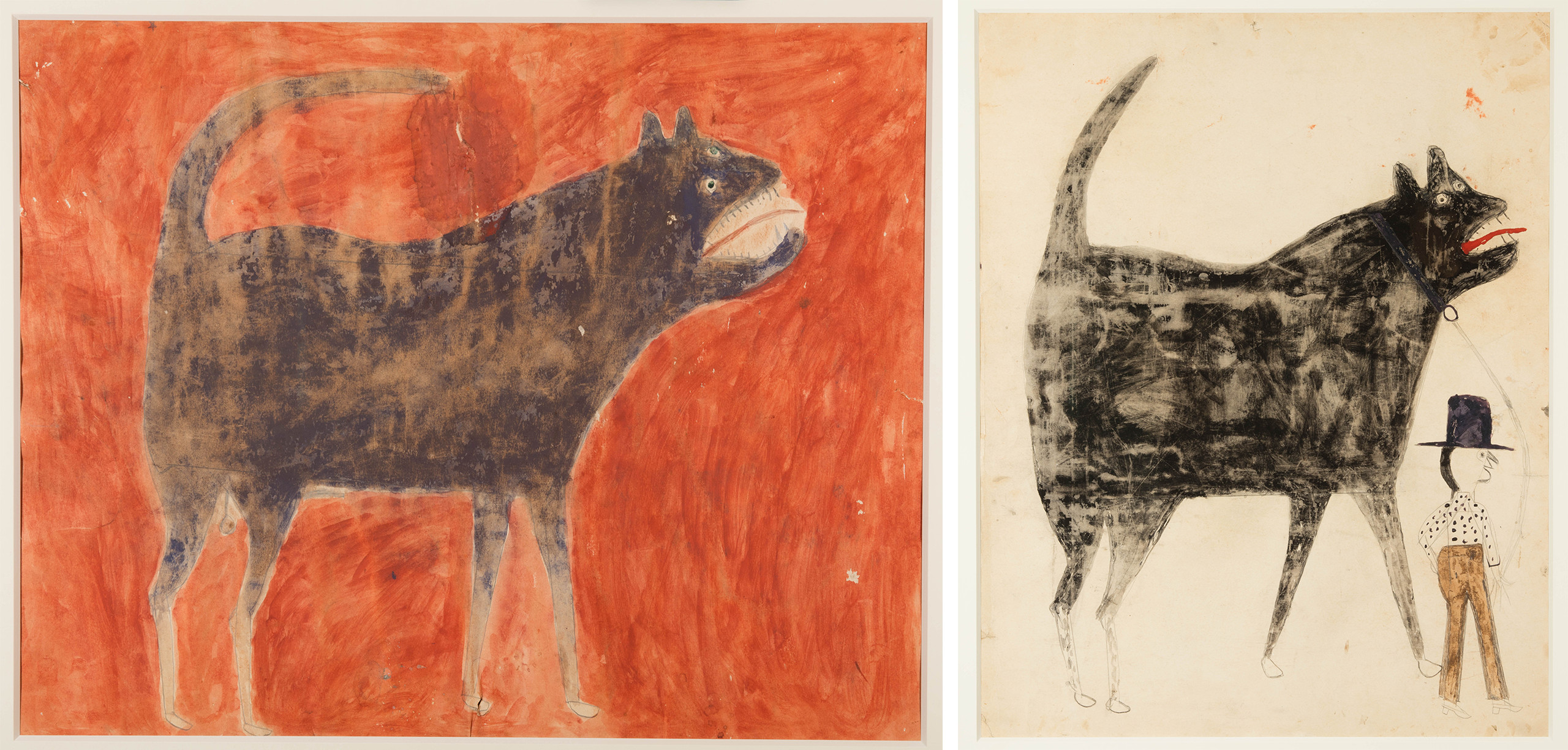

Mr. Lauren was drawn to the piece’s vividness and high contrast (“His use of color is a religion of sorts,” he says), but when he learned Traylor’s backstory—that he was born into slavery in Montgomery, Alabama, that he didn’t even begin creating until he was 85 years old, only 10 years before his death, that many of Traylor’s 1,500 known works were sketched with discarded pencils and donated poster paint on salvaged candy and cereal boxes while Traylor was homeless—he was completely hooked. Piece by piece, he kept adding, with an eye toward the most vibrant works he could find. Twenty-five years later, he has acquired arguably the most significant private collection of Traylors in the world—fighting dogs, well-dressed men, leaping figures, abstract forms—which he now displays in his apartment on the Upper East Side.

“I don’t brag about myself, but my collection? I do.” Lauren says, laughing. “I have 20 Traylors now, and they’re all worthy of a museum.”

Fittingly, 10 of those works have found a temporary home at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in the exhibition Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, the first major retrospective ever staged for an artist born into slavery. The show, which runs through March 17, 2019, was organized by Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The exhibition completes a seven-year journey to distill the prolific, self-taught artist’s oeuvre into 155 representative pieces, organized by recurring themes such as “The Dogs,” “Drinkers and Dancers,” and “Folk Magic, Dreams, and Transformation.” (Two more works from Lauren’s collection are featured in an accompanying monograph, published earlier this year.)

According to Umberger, the title Between Worlds refers to the uniquely disparate spheres Traylor navigated during his lifetime—slavery and freedom, black and white culture, rural and urban life. Like many former slaves, Traylor never learned to read or write, so his work is, as Umberger calls it, an oral history in visual form, one that ends on the cusp of the Civil Rights movement.

“Traylor’s intentions were to make a record of himself, to tell his own story, which was in and of itself a radical act,” explains Umberger, “because there were a number of people in segregated Montgomery who would have begrudged him holding a pencil, let alone expressing a personal point of view. In an era in which any breach of social etiquette could cost you your life, making drawings that expressed himself—that was a dangerous thing.”

As Lauren sees it, that courage, as well as the use of allegory and symbolism in exploring the African American experience, from the plantation to the Jim Crow South, position Traylor among the most important figures in the history of United States contemporary art. Umberger credits Lauren with helping to present Traylor’s story in full for the first time. “Jerry was an important resource,” she says. “Some of the pieces he owns were absolutely critical.”

Of course, Lauren was happy to lend his collection to the Smithsonian, and to shine a light on an artist whose contributions to the art world have been underappreciated for too long. “Traylor took my love of folk art to a new level,” he says, “though I hate that term—it’s American art. The breadth of his work involves so many creative ideas. The way he used shapes, captured positions, and depicted forms, almost like dance figures, it’s miraculous.”

Lauren did, however, experience some trepidation at the thought of being without his favorite works until spring of next year. As luck would have it, he doesn’t have to, thanks to the museum’s painstaking efforts to create exact photographic reproductions, which were matted, framed, and hung in the same spots as the originals in his Manhattan apartment.

“Leslie came over a few times and said, ‘I want to borrow this, this, this, and this.’ I told her, ‘I live with these every day. I see them every morning, and I put them to sleep at night!’” recalls Lauren with a laugh. “But the reproductions are fantastic. Without them, I would have been dying. It would have been like, ‘The kids are away at camp! When are they coming home!?’”

Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor—the first major retrospective ever organized for an artist born into slavery—runs through March 17, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

- BLACKSMITH SHOP, BY BILL TRAYLOR, CA. 1939–1940, PENCIL ON CARDBOARD

- THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK, GIFT OF EUGENIA AND CHARLES SHANNON. IMAGE COPYRIGHT © THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART. IMAGE SOURCE: ART RESOURCE, NY19

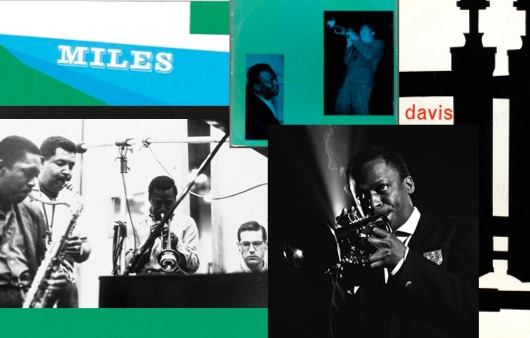

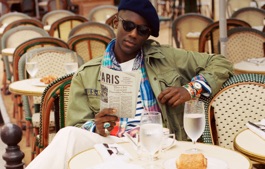

- COURTESY OF GETTY IMAGES

- THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK, GIFT OF EUGENIA AND CHARLES SHANNON. IMAGE COPYRIGHT © THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART. IMAGE SOURCE: ART RESOURCE, NY19