For Art’s Sake

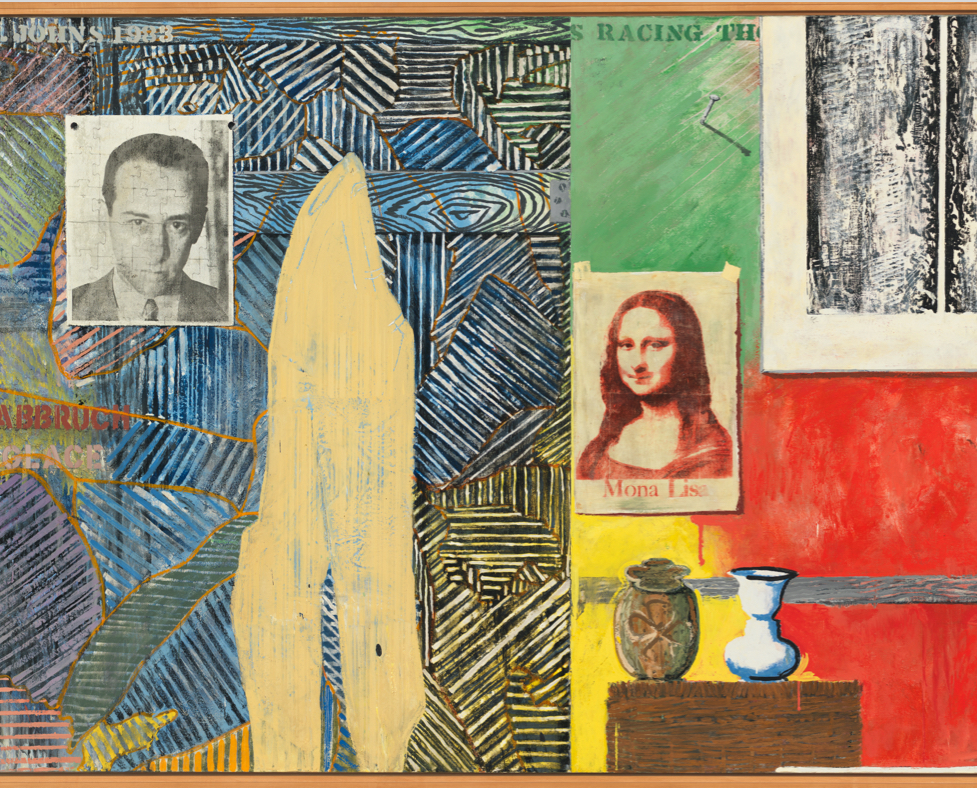

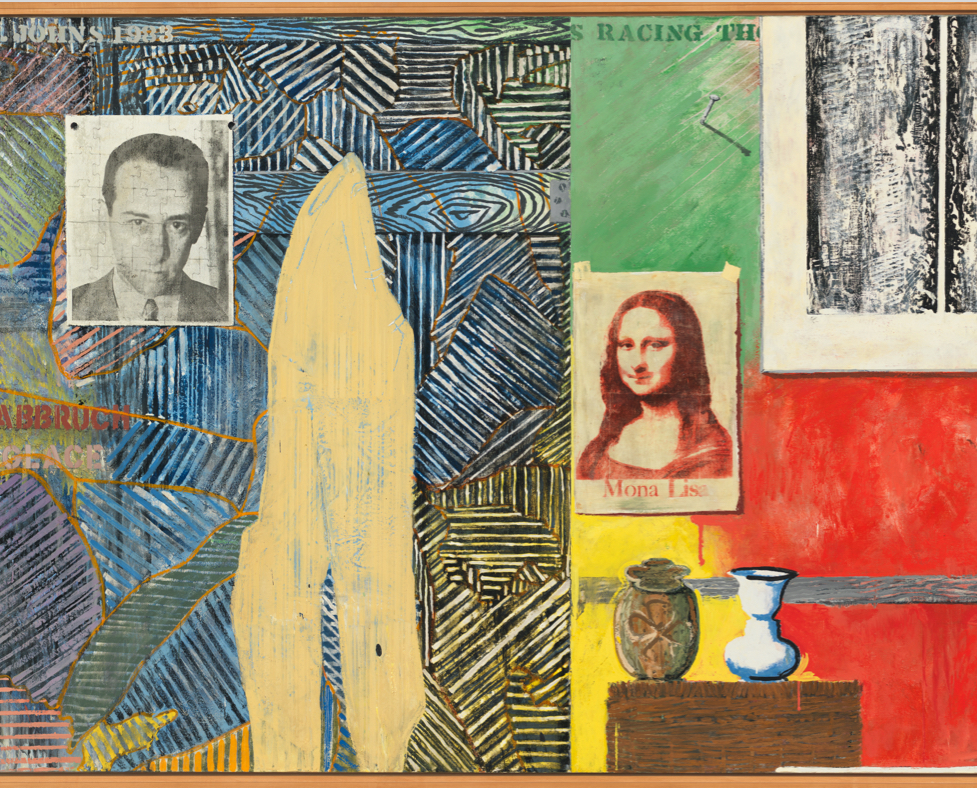

After a hiatus, New York’s art world is back in true form. Below, seven of our favorite boundary-pushing shows to inspire, teach, and make you dreamWho: Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror Where: Whitney Museum of American Art When: Until February 13, 2022

At 91, it’s difficult to tell if Jasper Johns is thinking about his legacy, but museums certainly are. As recently as 2018, The Broad in Los Angeles featured a major retrospective with 120 of his works. And this fall, the Whitney and the Philadelphia Museum of Art are co-hosting Mind/Mirror, an exhaustive retrospective featuring almost 500 paintings, sculptures, prints, and drawings, beginning with his famous flag paintings. American art, and the American gaze, are up for grabs in these works. They date back to the 1950s, when Johns firmly rejected the fierce, splashy, modes of abstract expressionism that dominated the New York art world. He used well-known symbols, like the flag and targets, as vehicles for an interior personal dialogue. Wordplay was another popular motif. You will recognize these works, and what’s depicted, where notions of memory versus reality, and image versus perception, push and pull on each other through seven decades. Within his brushstrokes and language, you find a prankster, a jokester, and a philosopher at work. What you see isn’t what you get—the mirror and the mind are never quite aligned—and in that tension we find the space to explore who we are.

Who: Curran Hatleberg Where: Higher Pictures Generation When: Until November 27, 2021

One of the most exciting photographers working today, here Curran Hatleberg takes his talent on the road. Following in the footsteps of Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, and Ryan McGinley, the artist explores America by car, “to photograph the slough of the white man’s American Dream,” says curator Marina Chao. What’s interesting about these photographs is that said “man” is barely present. Hatleberg’s work has delved deep into interactions between people, or people and their surroundings. In a move more easily compared to Ed Ruscha’s road work than Robert Frank’s, we see landscapes and imagery nearly devoid of human presence: A literal open road; a dog makes its way through a torn screen door; an alligator carcass dangles. At this post-pandemic moment of reassessment, when many of us are taking stock of our values, relationships, and where we stand in relation to the world around us—Hatleberg included—he is forcing us to contemplate space and place; what we’ve shed and where we’ve gone. Seeing these photos, you can’t help but ask the big questions, beginning with: “Where am I?”

Who: Robert Rauschenberg: Channel Surfing Where: Pace Gallery When: Until Oct 23, 2021

An important thing you should know about the later work of Robert Rauschenberg—whose “combines” (three-dimensional mixed-media works) of the 1950s and 1960s flipped the switch on collage, painting, and sculpture—is that the TV was always on in his studio, but the volume was almost always off. This exhibit looks at Rauschenberg’s later output, from the last 25 years of his life (he died in 2008), and his return to paint and sculpture. While artists from the Pictures Generation, like Richard Prince, borrowed from other sources, Rauschenberg, a pioneer of appropriation, did the exact opposite, using his own photos. At the same time, he worked in an era when cable TV, globalization, and mass imagery are inescapable. The work might become more autobiographical, but like the TV in his studio, the world is never far away. In Channel Surfing, one of America’s great innovators makes a final push at the boundaries of art through a return to painting and sculpture made from found objects. “This is the story of Rauschenberg reinventing himself,” says Pace curatorial director Oliver Shultz, “but returning to an earlier language at the same time.”

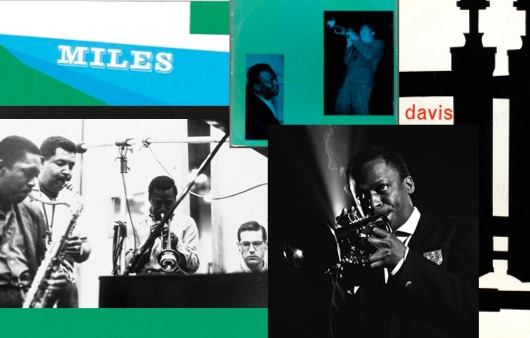

Who: LeRoy Neiman: What’s the Score? The Posters of LeRoy Neiman Where: Poster House When: Until March 27, 2022

Once, when Frank Sinatra was asked about his dreams, he said that they were in the colors of LeRoy Neiman. Neiman, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year, was famous for illustrating American sports and other leisure activities in his vivid, kinetic style. His are rich figurations that don’t only place you in the action, but encapsulate an entire sport, or the spirit of a performance. This fall, you can catch them in all their glory at Poster House, thanks to a gift of more than 100 works from the LeRoy Neiman Foundation. Here you’ll see Sinatra, Muhammad Ali, and other icons of American culture (many of whom were Neiman’s friends as well as muses). But better than the famous faces are Neiman’s distinctive, action-driven style of the jazz musicians, golfers, tennis players, and Olympians he draws. “He’s catching someone,” says Tara Zabor, executive director of the LeRoy Neiman Foundation. “If you look at the pole vaulter, they’re midair; your mind takes you through the rest of that movement. He’s bringing you into the acme of the action that’s occurring.” These posters aren’t just iconic, they’re exciting.

Who: Etel Adnan: Light’s New Measure Where: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum When: Until January 10, 2022

Etel Adnan once took on an entire language. In the 1950s, when Adnan was a philosophy professor in California, and France ruled Algeria, the Lebanese-born novelist, journalist, poet, and artist rejected any further writing in French. From then on, in her words, she would “paint in Arabic.” A strong sense of moral and social justice flows through much of Adnan’s written work, and though her large geometric landscapes might look like simpler distillations, there are worlds in these moments. A single slice of blue becomes the Pacific Ocean; we see the outline of Mount Tamalpais, never far from her perspective at her home in Sausalito, California. It’s her world, but also ours. Etel uses her impressions—geometric landscapes that fall somewhere between figurative and abstract—to express human potential through our natural world. These are works made without flourish or finish but with absolute intention, precision, and power. As you make your way up the the first two levels of Frank Lloyd Wright’s rotunda, Adnan’s paintings, tapestries, and drawings, with their repeated shapes, take the smallest moments and allow us to see how to see how one scene, one glimpse, can order, or disorder, all that is.

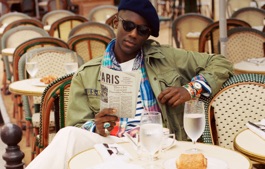

Who: Rashid Johnson Where: Storm King When: Ongoing

There are as many reasons to visit Storm King on a fall day as there are leaves on the trees (or the ground, depending on when you make it there). It is the perfect day trip from New York City, and it is difficult to find a comparable collection of large-scale work, from such storied sculptors, in a single place (they’re all here: Louise Bourgeois; Alexander Calder; Mark di Suvero; Sol LeWitt). One of the newest additions, a piece by Rashid Johnson, has been on loan since April of 2021. Called “Crisis”—named for Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, an influential book from the Civil Rights movement—the 16-foot tall grid of bright yellow steel sits in one of Storm King’s fields and speaks as much to our time as that one. Johnson built the piece in 2019, when discussions about the “crisis at the border” were on the news each day. The sturdy painted lattice, both out of place and totally fitting in this field, speaks to danger, and fear, and to the spaces we can and cannot occupy. Welcoming, but impenetrable, this is large-scale sculpture at once magnificent, complex, and terrifying.

Who: Katelyn Eichwald: Never Where: Fortnight Institute When: Until October 24, 2021

There’s a mystery to Katelyn Eichwald’s work. These paintings are haunting, and yet pregnant with possibility. They are hazy and dreamlike, but at the same time they’re eerily precise. A noose lays coiled in on itself on the floor. An elegant finger pulls at a sleeve to examine the face of a classic watch. These are noir films with a touch of horror being acted out on canvas. Eichwald uses oil paint, but creates a vaporous, smoky texture by using small round brushes. She lets the paint seep deeply into the fabric, almost like a stain. In these dark schemes, there are characters outside of the ones you might imagine, but the tension is ever-ready; the stakes always sky high. “When you look at her works, there’s no resolution,” says Fabiola Alondra, Fortnight’s co-director. “It leaves you hanging on an edge, and that’s part of being pulled into the works. Also, they’re very cinematic, but I like that they’re not loud. They’re subtle. There’s something very sinister that I love.” You’ll love it too.

Who: Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror Where: Whitney Museum of American Art When: Until February 13, 2022

At 91, it’s difficult to tell if Jasper Johns is thinking about his legacy, but museums certainly are. As recently as 2018, The Broad in Los Angeles featured a major retrospective with 120 of his works. And this fall, the Whitney and the Philadelphia Museum of Art are co-hosting Mind/Mirror, an exhaustive retrospective featuring almost 500 paintings, sculptures, prints, and drawings, beginning with his famous flag paintings. American art, and the American gaze, are up for grabs in these works. They date back to the 1950s, when Johns firmly rejected the fierce, splashy, modes of abstract expressionism that dominated the New York art world. He used well-known symbols, like the flag and targets, as vehicles for an interior personal dialogue. Wordplay was another popular motif. You will recognize these works, and what’s depicted, where notions of memory versus reality, and image versus perception, push and pull on each other through seven decades. Within his brushstrokes and language, you find a prankster, a jokester, and a philosopher at work. What you see isn’t what you get—the mirror and the mind are never quite aligned—and in that tension we find the space to explore who we are.

Who: Curran Hatleberg Where: Higher Pictures Generation When: Until November 27, 2021

One of the most exciting photographers working today, here Curran Hatleberg takes his talent on the road. Following in the footsteps of Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, and Ryan McGinley, the artist explores America by car, “to photograph the slough of the white man’s American Dream,” says curator Marina Chao. What’s interesting about these photographs is that said “man” is barely present. Hatleberg’s work has delved deep into interactions between people, or people and their surroundings. In a move more easily compared to Ed Ruscha’s road work than Robert Frank’s, we see landscapes and imagery nearly devoid of human presence: A literal open road; a dog makes its way through a torn screen door; an alligator carcass dangles. At this post-pandemic moment of reassessment, when many of us are taking stock of our values, relationships, and where we stand in relation to the world around us—Hatleberg included—he is forcing us to contemplate space and place; what we’ve shed and where we’ve gone. Seeing these photos, you can’t help but ask the big questions, beginning with: “Where am I?”

Who: Robert Rauschenberg: Channel Surfing Where: Pace Gallery When: Until Oct 23, 2021

An important thing you should know about the later work of Robert Rauschenberg—whose “combines” (three-dimensional mixed-media works) of the 1950s and 1960s flipped the switch on collage, painting, and sculpture—is that the TV was always on in his studio, but the volume was almost always off. This exhibit looks at Rauschenberg’s later output, from the last 25 years of his life (he died in 2008), and his return to paint and sculpture. While artists from the Pictures Generation, like Richard Prince, borrowed from other sources, Rauschenberg, a pioneer of appropriation, did the exact opposite, using his own photos. At the same time, he worked in an era when cable TV, globalization, and mass imagery are inescapable. The work might become more autobiographical, but like the TV in his studio, the world is never far away. In Channel Surfing, one of America’s great innovators makes a final push at the boundaries of art through a return to painting and sculpture made from found objects. “This is the story of Rauschenberg reinventing himself,” says Pace curatorial director Oliver Shultz, “but returning to an earlier language at the same time.”

Who: LeRoy Neiman: What’s the Score? The Posters of LeRoy Neiman Where: Poster House When: Until March 27, 2022

Once, when Frank Sinatra was asked about his dreams, he said that they were in the colors of LeRoy Neiman. Neiman, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year, was famous for illustrating American sports and other leisure activities in his vivid, kinetic style. His are rich figurations that don’t only place you in the action, but encapsulate an entire sport, or the spirit of a performance. This fall, you can catch them in all their glory at Poster House, thanks to a gift of more than 100 works from the LeRoy Neiman Foundation. Here you’ll see Sinatra, Muhammad Ali, and other icons of American culture (many of whom were Neiman’s friends as well as muses). But better than the famous faces are Neiman’s distinctive, action-driven style of the jazz musicians, golfers, tennis players, and Olympians he draws. “He’s catching someone,” says Tara Zabor, executive director of the LeRoy Neiman Foundation. “If you look at the pole vaulter, they’re midair; your mind takes you through the rest of that movement. He’s bringing you into the acme of the action that’s occurring.” These posters aren’t just iconic, they’re exciting.

Who: Etel Adnan: Light’s New Measure Where: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum When: Until January 10, 2022

Etel Adnan once took on an entire language. In the 1950s, when Adnan was a philosophy professor in California, and France ruled Algeria, the Lebanese-born novelist, journalist, poet, and artist rejected any further writing in French. From then on, in her words, she would “paint in Arabic.” A strong sense of moral and social justice flows through much of Adnan’s written work, and though her large geometric landscapes might look like simpler distillations, there are worlds in these moments. A single slice of blue becomes the Pacific Ocean; we see the outline of Mount Tamalpais, never far from her perspective at her home in Sausalito, California. It’s her world, but also ours. Etel uses her impressions—geometric landscapes that fall somewhere between figurative and abstract—to express human potential through our natural world. These are works made without flourish or finish but with absolute intention, precision, and power. As you make your way up the the first two levels of Frank Lloyd Wright’s rotunda, Adnan’s paintings, tapestries, and drawings, with their repeated shapes, take the smallest moments and allow us to see how to see how one scene, one glimpse, can order, or disorder, all that is.

Who: Rashid Johnson Where: Storm King When: Ongoing

There are as many reasons to visit Storm King on a fall day as there are leaves on the trees (or the ground, depending on when you make it there). It is the perfect day trip from New York City, and it is difficult to find a comparable collection of large-scale work, from such storied sculptors, in a single place (they’re all here: Louise Bourgeois; Alexander Calder; Mark di Suvero; Sol LeWitt). One of the newest additions, a piece by Rashid Johnson, has been on loan since April of 2021. Called “Crisis”—named for Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, an influential book from the Civil Rights movement—the 16-foot tall grid of bright yellow steel sits in one of Storm King’s fields and speaks as much to our time as that one. Johnson built the piece in 2019, when discussions about the “crisis at the border” were on the news each day. The sturdy painted lattice, both out of place and totally fitting in this field, speaks to danger, and fear, and to the spaces we can and cannot occupy. Welcoming, but impenetrable, this is large-scale sculpture at once magnificent, complex, and terrifying.

Who: Katelyn Eichwald: Never Where: Fortnight Institute When: Until October 24, 2021

There’s a mystery to Katelyn Eichwald’s work. These paintings are haunting, and yet pregnant with possibility. They are hazy and dreamlike, but at the same time they’re eerily precise. A noose lays coiled in on itself on the floor. An elegant finger pulls at a sleeve to examine the face of a classic watch. These are noir films with a touch of horror being acted out on canvas. Eichwald uses oil paint, but creates a vaporous, smoky texture by using small round brushes. She lets the paint seep deeply into the fabric, almost like a stain. In these dark schemes, there are characters outside of the ones you might imagine, but the tension is ever-ready; the stakes always sky high. “When you look at her works, there’s no resolution,” says Fabiola Alondra, Fortnight’s co-director. “It leaves you hanging on an edge, and that’s part of being pulled into the works. Also, they’re very cinematic, but I like that they’re not loud. They’re subtle. There’s something very sinister that I love.” You’ll love it too.

- Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art

- Courtesy of Higher Pictures Generation

- Courtesy of Pace Gallery

- Courtesy of Poster House

- Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- Courtesy of Storm King

- Courtesy of Fortnight Institute