Appetite for Destruction

The rising artist Fabian Oefner loves well-designed things, from classic cars to iconic shoes. As a recent collaboration with Polo revealed, demolition can be an act of recreationMaybe you’ve seen Fabian Oefner’s work on Instagram: photos and videos of iconic consumer products that have been sliced, diced, melted, blown up, encased in a transparent cube, or surreally embedded in a wall.

Most of the objects are icons of popular design - a familiar laptop model, a famous sneaker, a Moka pot - that Oefner has savaged in carefully premeditated fashion. His work gets your attention the way a train wreck or news of an awful crime does. Once you get over the initial shock and awe of it, though, you begin to see the object of his attention differently, and to develop a newfound sympathy and respect for it.

Oefner, who is 39 and studied product design in his native Switzerland, explains that he’s “trying to do justice to the object.” Enormous amounts of intelligence and hard work go into the execution of good design, and he wants to honour that. When he smashes something to bits, he says, “It’s a very precise explosion - which is a contradiction, but I like that.”

Contradictions aside, there is something contained and approachable about Oefner’s work, which fetches prices from the “high four-digit numbers” to more than $100,000. He doesn’t challenge our consumer fetishes, much less vandalise them the way punk predecessors have; the contents of his resin boxes are less unsettling than Damien Hirst’s infamous shark, suspended in a vat of formaldehyde. He takes Daniel Arsham’s view of technology as artifact, but also has an engineer’s curiosity about how it works.

Talking in his studio - a converted hat factory in Danbury, Connecticut, just 10 minutes from where he lives with his wife - Oefner comes across as more thoughtful than mad scientist. The corner of the States that he’s chosen for his experiments is an old New England factory town with no art scene to speak of. (There is, however, a legit dive bar across the street, and a disconcerting amount of razor wire.) What Oefner likes about Danbury is that it lacks the distractions and space constraints of New York City. He has 5,000 square feet (which he shares with just one assistant) to pace around. During the time it takes to walk from one end to the other - past his 3D printer, ping-pong table, photo studio-within-a-studio, and power saws comfortably spaced atop sawhorse tables - a whole new idea can germinate. It’s the perfect base for a creative split personality who describes himself as a “9-year-old boy who likes to blow stuff up combined with a 40-year-old philosopher who likes to think about time.”

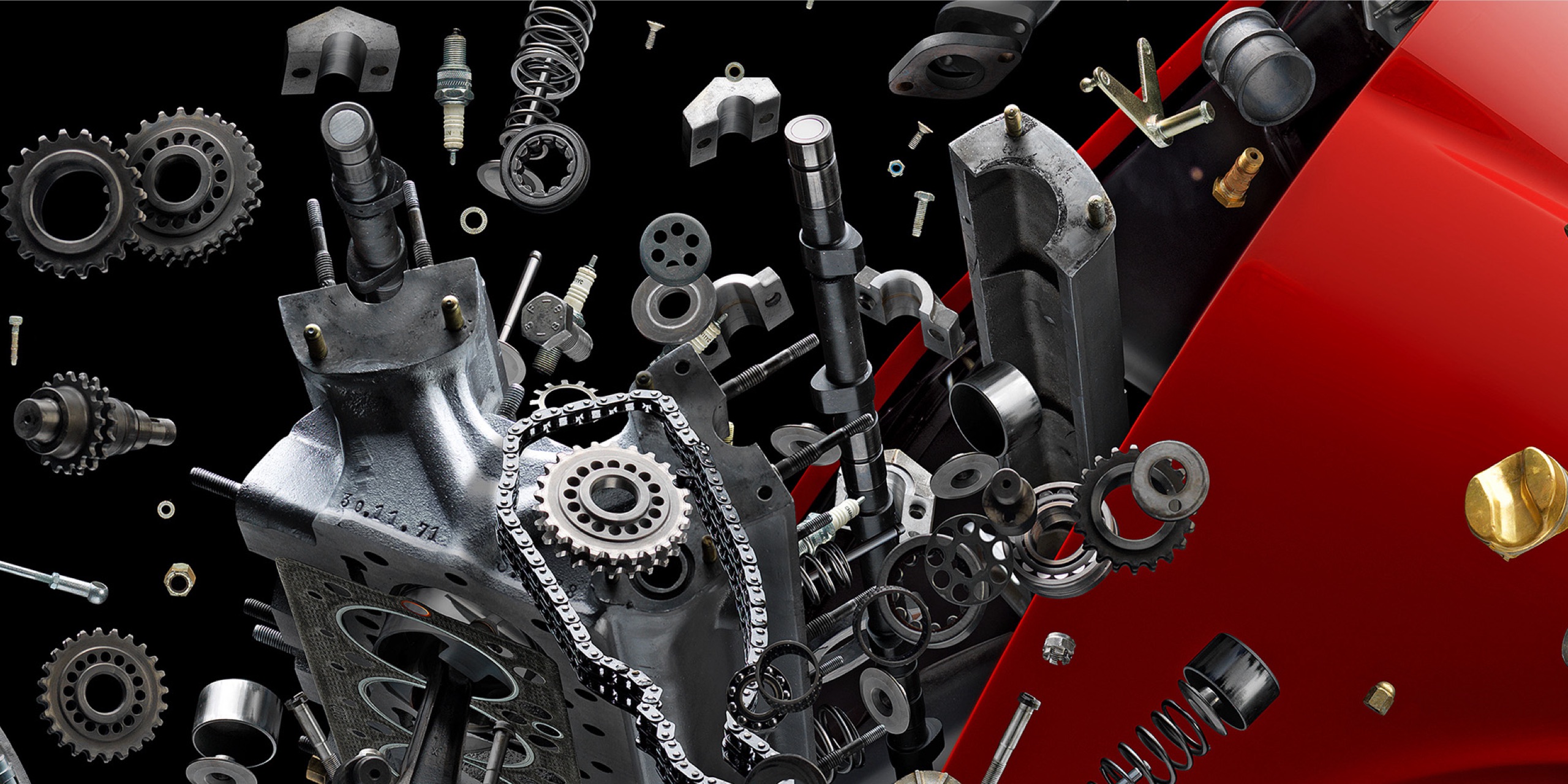

Oefner has photographed the component parts of a number of legendary cars, including, at top, a 1938 Bugatti Atlantic, and collaged them into images that make it appear as if the object is disintegrating

A 1972 Lamborghini Miura gets the Oefner treatment, one piece at a time

A 1972 Lamborghini Miura gets the Oefner treatment, one piece at a time

A 1972 Lamborghini Miura gets the Oefner treatment, one piece at a time

Over a couch in the sitting area hangs one of his most celebrated results: a roughly 8-by-4-foot photo of a 1972 Lamborghini Miura eruptively coming apart at both ends. Rest assured that no Lambos were harmed in the making of this artwork. Oefner set up his camera alongside a team of Italian mechanics while they restored the car for its owner, photographed some 1,500 components as each was removed, and collaged them into a hyper-real image of the Miura basically projectile vomiting its guts out. Part of his “Disintegrating” series, the piece is from an edition of five (the other four have been sold). It took two years to create.

Oefner grew up outside of Basel, where his mother worked in an art gallery and his father was a chef. “I was always a very curious person. As a kid, I would basically confiscate the attic and turn it into a kind of science lab, using photography to capture what I saw,” he says. He was working as a product photographer for Leica when his off-hours experiments started getting enough attention for him to become a full-time artist. His work is now in private collections from Brazil to Hong Kong, Los Angeles to Dubai. M.A.D., a gallery in Geneva, handles his car-themed art, but otherwise he’s unrepresented. Collectors reach out to him by DM.

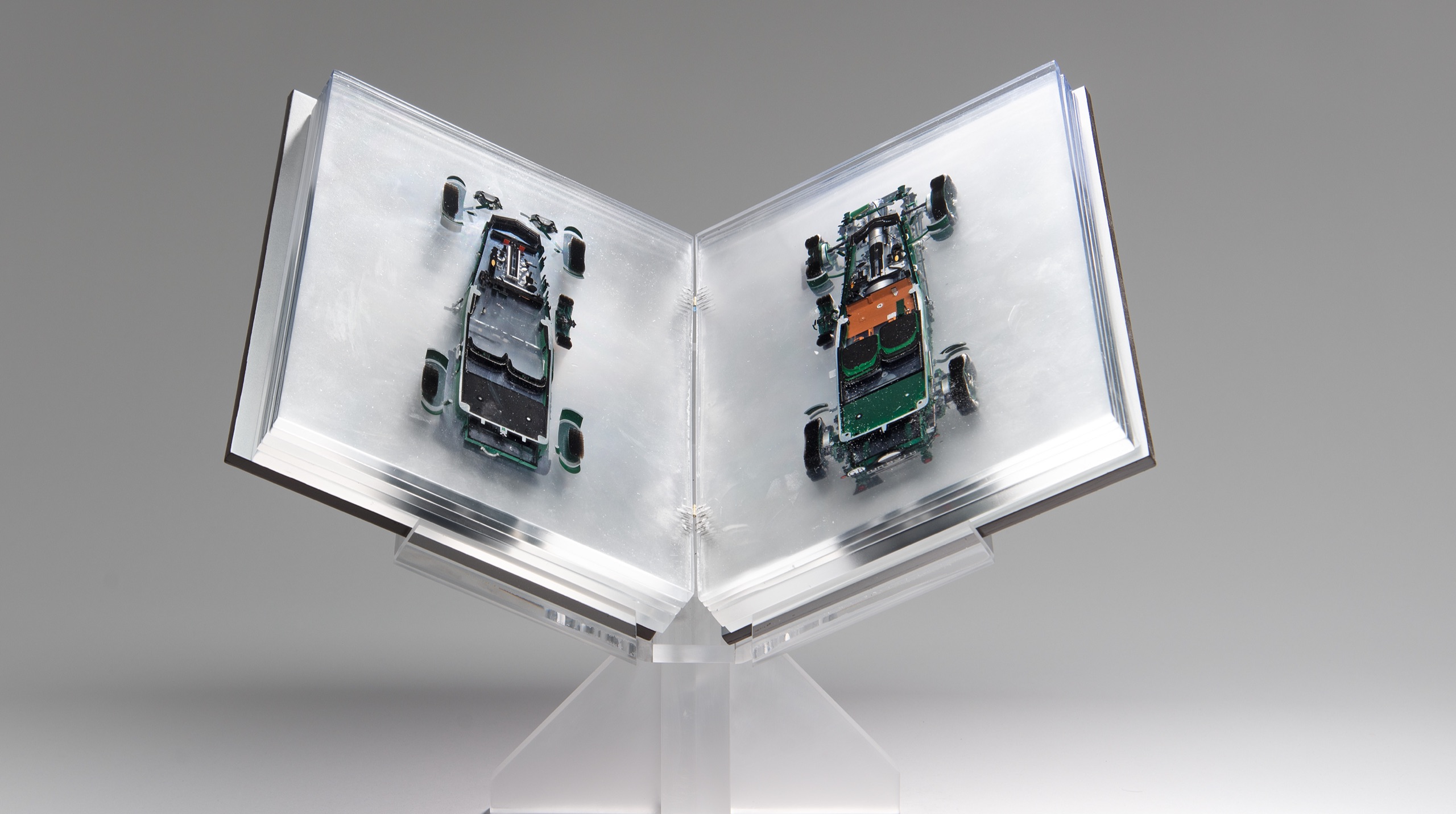

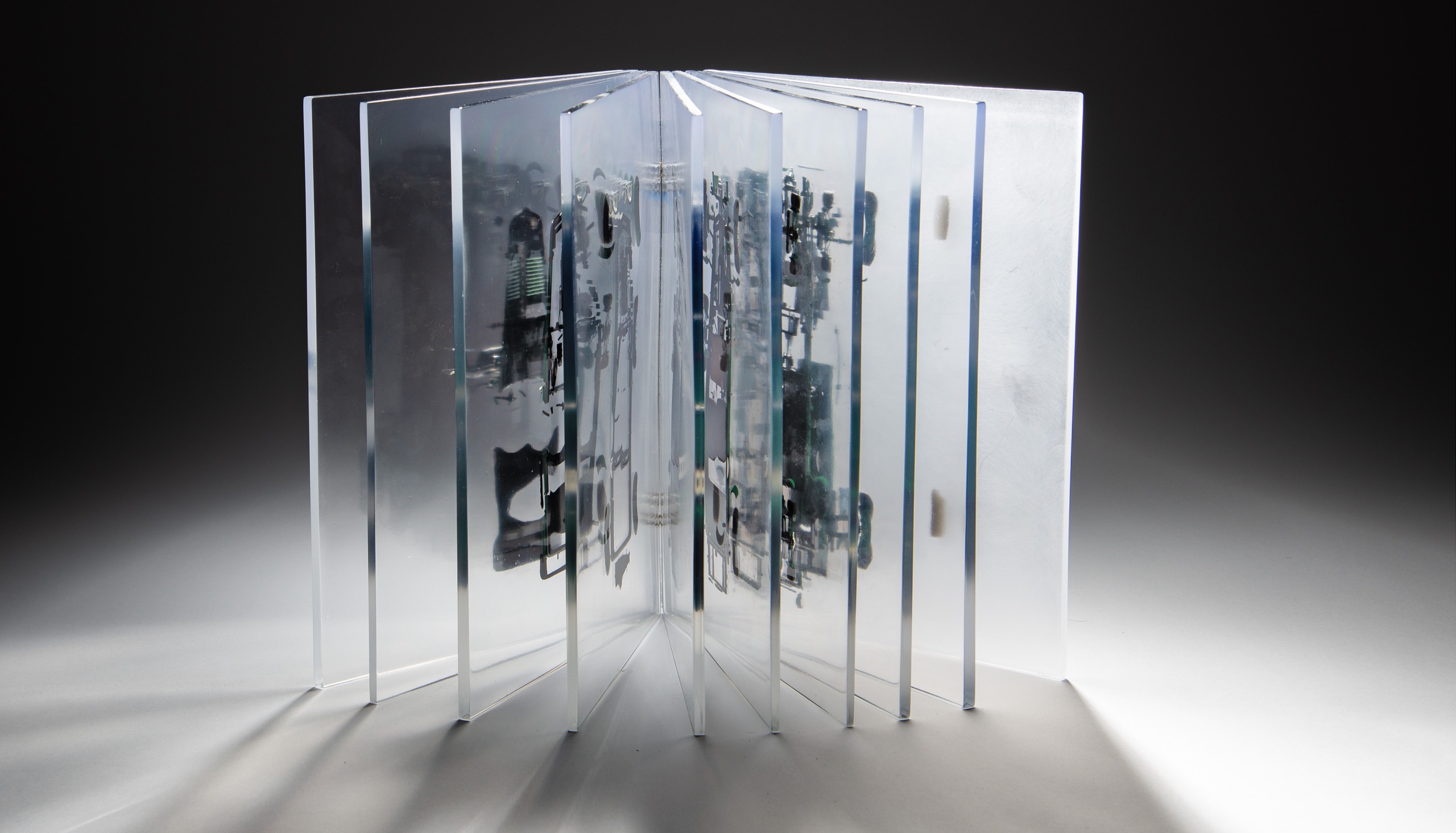

One of Oefner’s ongoing projects is what he calls Spatial Books, inspired by the herbariums he used to make in biology class. Rather than press leaves or plants on paper, he first encases the object he has selected - a vintage Brionvega radio, say, or a Nike Warrior sneaker - in a block of clear resin. Then, after the material has set, he painstakingly slices the result into a series of cross sections, or pages, that he binds together like a book. “It is about distorting reality, which is another big topic in my work,” he says of transforming an object from three dimensions into two. In one sense, he destroys the object: the sliced-up radio is silent; the futuristic athletic shoe can’t be worn. In another sense, he both preserves and creates a new way of looking at such iconic things.

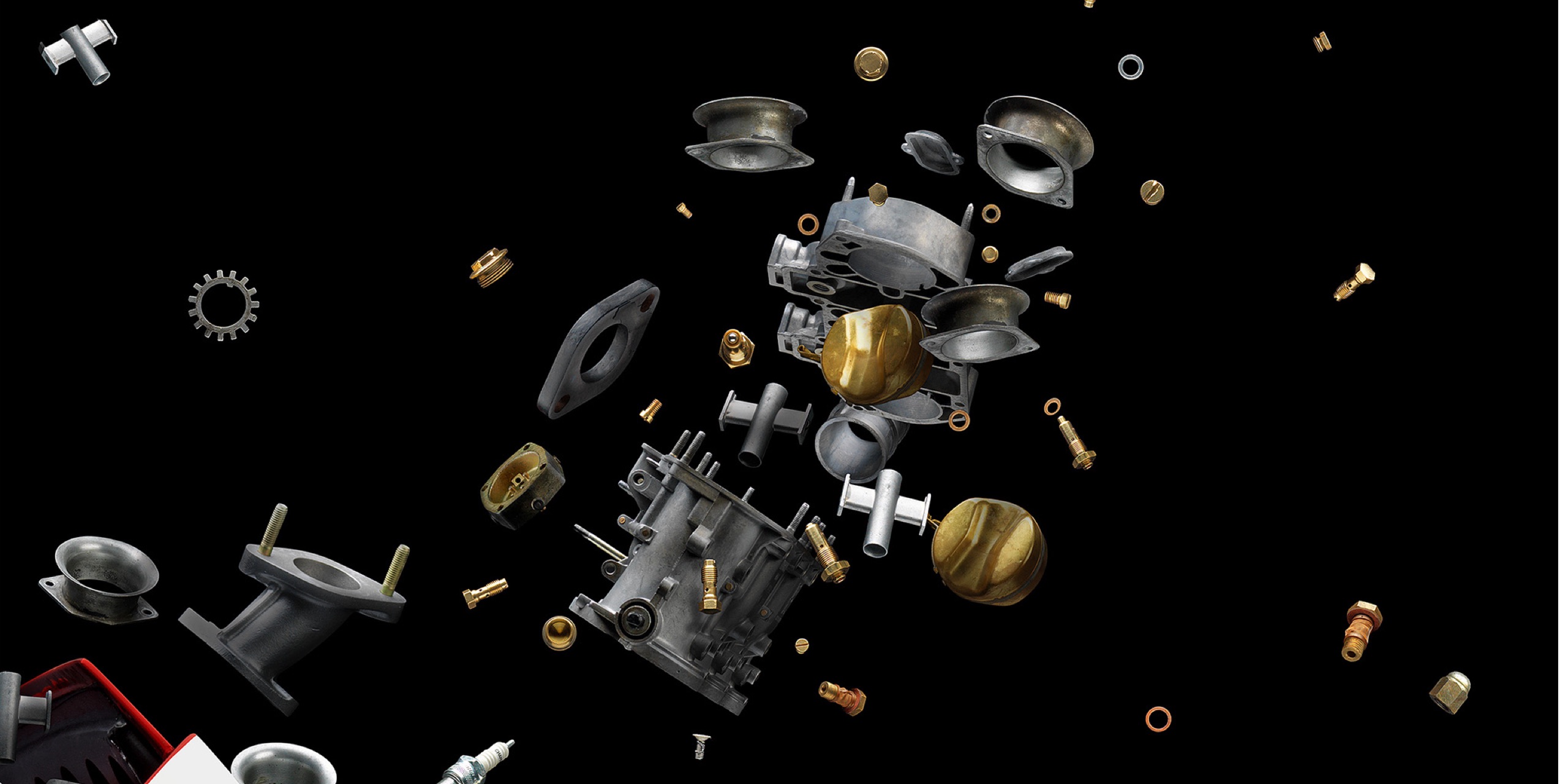

Earlier this fall, Ralph Lauren commissioned Oefner to make a Spatial Book of a Bentley Blower, a supercharged (and now super-rare) relic of the interwar auto-racing period. Oefner never laid hands on Ralph’s own 1929 Blower, but the shoe-sized custom model that he worked from replicated the original in minute detail. In his studio, he shows me the keg-sized pressure chamber in which clear, gel-like resin hardened around the Blower overnight, and the bandsaw that he used to cut - very, very slowly - through the embalmed vehicle. Each pristine slice took two hours.

Oefner recently collaborated on a project with Polo that resulted in one of his “Spatial Books” and involved sawing a Bentley Blower into slices after it had been encased in a block of clear resin

The Blower may have put the roar in the Roaring Twenties. Here, though, the legendary car sometimes known as “the Beast” has been put on a kind of artistic-scientific display. Dissected with surgical precision, the Blower’s classic design comes to the fore. “As you cut through it, you realize it’s a carriage in disguise,” Oefner says: the elegant wood-and-leather frame, the “watchmaking quality of the gauges.” You can forget for a moment that the Blower pushed the limits of modernity, and see it more as an extension of the past.

Oefner spent many additional hours finishing this one-of-a-kind piece, hand-sanding the resin tablets and binding them in green faux leather. Bending materials and machines to his purpose requires the sort of patience and precision that Swiss craftsmen are known for, but there’s another aspect that feels more transgressive, more American. “Cutting into stuff - Swiss people don’t do that. They treat things with more delicacy, more respect,” Oefner says. “In the US, there’s more open-mindedness about art.”

Oefner walked me to the far end of the studio, where he was currently working on his latest non-commissioned piece: a bust copy of the Venus de Milo suspended in resin as though shattering into a thousand pieces. Oefner himself had smashed the famous head with a sledgehammer, then photographed the split-second moment of impact, and had recently finished recreating that instant shard by shard using an advanced technique that he prefers not to explain. He describes the result as a “moment frozen in time that you can walk around and see in three dimensions.” As we’re doing just that, the pre-rush-hour traffic on I-84 flows by outside the window - a surreal but temporary effect, Oefner jokes. “An hour from now, they’ll be standing still,” he says, as if describing one of his own snapshots in time.

MORE FROM THE POLO GAZETTE

Speed Painters

The greatest of Grand Prix posters achieve the unimaginable feat of freezing a race car in motion. Through the decades, few artists have done it better than these, and though prices for their work are on the rise, it’s still a buyer’s market

By Paul L. Underwood