A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN

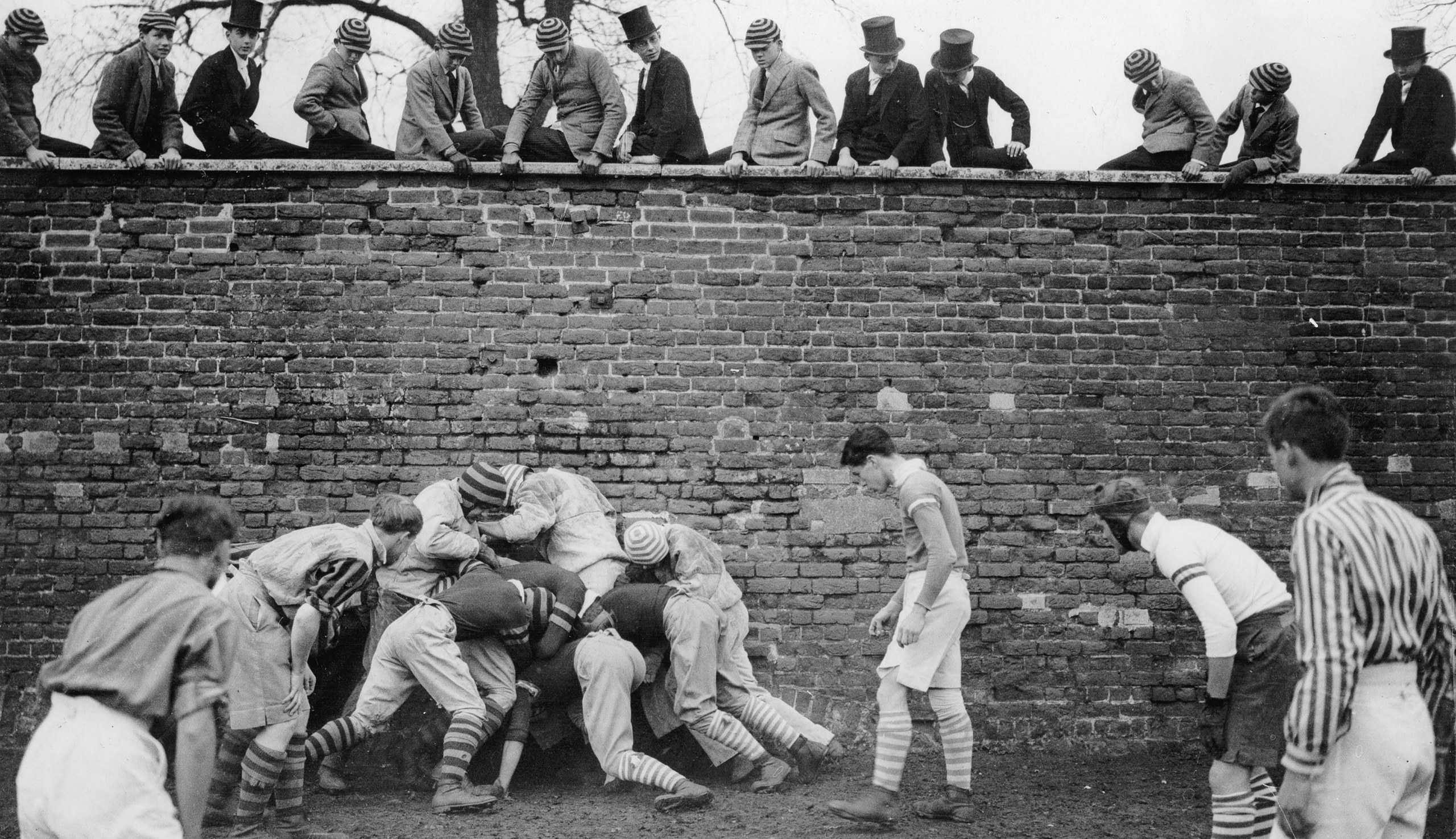

No furking allowed! But, there is post-game sponge cake. Welcome to the peculiar traditions of “the wall game” at England’s superelite Eton CollegeA knot of young men in striped shirts shove up against one another, heads down and grunting as other boys sitting atop a wall jeer and urge them on. The scene resembles a rugby scrum, or that moment in American football when a running back smacks into the opposing line—except that the struggle goes and on and on, the ball hidden beneath a muddy tangle of arms and legs, until the unacquainted spectator realizes that what he is witnessing is basically the whole game.

This organized hour of “constant, hand-to-hand, Homeric conflict,” as the British writer Arthur Clutton-Brock described it in the book Eton, is known as the wall game, and it’s been played for centuries at Eton, Britain’s most exclusive boys’ school.

Located an hour west of London, 580-year-old Eton occupies a special place in the national legend, and the school’s identity is inseparable from its prominent sporting culture. During the glory days of the British Empire, the Duke of Wellington famously claimed that the Battle of Waterloo had been won on the “playing fields of Eton”— that the country’s sturdiest leaders, in other words, had become men thanks to the character-building sports of their childhood.

Whether this observation is true or not, arcane ball sports remain a quirky rite of passage for boys of Britain’s ruling class. Quirkiest among these is the wall game, which is played at Eton and nowhere else. Various prime ministers have competed in it, and so did George Orwell—with great enthusiasm, no less. More recently, Prince Harry has emerged from its scrum and into manhood. As one of several predecessors to rugby and soccer, the wall game has plenty of broader historical relevance as well.

The Origins

The first recorded match was in 1766. The wall game was “well established” as a winter sport at Eton by the 1820s, and its rules were more or less codified by 1844, when the first St. Andrew’s Day match—a tradition to this day—was held. As the Victorian era got into full swing, the wall game became a central feature of life at Eton. Before, the masters had merely tolerated it as a way to keep rambunctious students within school bounds; now they championed it as a means of instilling toughness and team spirit at the highest levels of society. This generational shift in attitudes applied not just to the wall game but to sports in general: The revered Duke, a maker of the British Empire, is said to have uttered his famous quote while watching a cricket match.

The Rules

Now might be a good time to explain how the wall game is played. The action unfolds along a 120-yard wall, making its field of play about as long as an American football field. At 15 feet wide, however, the “furrow”—the stretch of playable terrain—is considerably narrower. Most of the excitement happens along the wall as the leather ball remains locked in the scrum, or “bully.” Opposing teams try, without using hands, to move the ball toward the opposing end zone, or “calx.” Once there, if a team manages to prop the ball up against the wall and touch it with a hand, it has scored a “shy.” The goal at one end is a door; at the other end it’s an ancient elm tree—or at least it was, until recent decades. Now it’s a discreet chalk mark. Goals are worth nine points, and extremely rare. Shies are worth one.

The wall game is “as brutal in appearance as it is difficult to follow,” writes Nick Fraser in The Importance of Being Eton. But there’s more going on than meets the eye—and not all of it is legal. “Sneaking,” a version of offsides, is not allowed. Nor is “furking,” or dragging the ball out of the bully in a backward direction. “Knowing how not to breach the rules, or how to call out the other side for a breach, can prove critical” to success, explains London barrister Nico Leslie, who was at Eton from 1997 to 2002 and played opposite Prince Harry. “One tactic was to make sure your gloves were nicely roughed up, and then twist the gloves back and forth in the opponent’s face,” he adds. “This could get quite uncomfortable.” Though some face-mashing is tolerated, eye-gouging and punching aren’t.

More preparation than usual—not to mention press attention—accompanies the St. Andrew’s Day match, which takes places every November. It pits a 10-man team of Collegers, or scholarship students, against Oppidans, the name for the school’s full-tuition majority. The player pool for Oppidans is larger, exponentially so. (The ratio nowadays is around 14-to-1.) But this numerical advantage is offset by the fact that Collegers are housed together next to the wall and thus get much more opportunity to practice—and arguably have more pride at stake. As the only formal match of the year, this one is “taken very seriously,” says Malachi Mills, a current Eton student. This is especially true for the players, who are more or less performing in front of the whole school. (Nonetheless, the last time anyone scored a goal on St. Andrew’s Day was 1909.)

Each of the four recognized wall game teams wears its own colors. The kits are beyond retro, consisting of bold prison stripes and matching socks and caps. Colleger jerseys are white and purple, while Oppidans wear orange and purple. Oppidans will wear white sporting trousers on St. Andrew’s Day, a country-club accent that contrasts with the “war paint” they apply to their faces for the big match.

As with rugby, padding is skimpier than one might expect. Gloves are common, but otherwise the only areas that a player might choose to protect are his mouth—by means of a mouthguard—and his lower leg. Where earlier students might have wrapped book bindings inside their trousers to achieve the latter, today’s players opt for standard shin pads.

The Legacy

Eton’s wall game is itself an architectural variation, so to speak, on another game that is still played there today: the field game. Though older than the wall game, it has more of the flow of modern ball sports, and lots of students prefer it. “Field game is a much freer, faster game, which I find more fun,” Mills says. Each team’s back line aims to kick the ball downfield so that the other players can advance with it and score a goal, or “rouge.”

More Eton students play the field game than the wall game; there are regular contests between houses and none of the fancy banquets or overtly classist rivalries of the St. Andrew’s Day wall game. Adds Mills: “People remember the score, unlike in wall game, where many don’t even know the score by the end.”

- Courtesy of Getty Images

- Illustrations by Lachlan Campbell from Eton Colours: An Essential Illustrated Aide Memoire; @lachlancampbellartist