Drive up the Beaverkill Valley on a sunny June day and your heart will sing. I know mine was crooning at every glimpse of hemlock-shaded trout stream and tidy farmhouse on this tony stretch of the Catskills. Whether they are Victorian-era vacation homes or impeccable reproductions of such, the houses up here are invariably white with green trim and a wraparound porch that’s perfect—in normal times, at least—for gathering a group of friends for gin and tonics.

As we all know, these are not normal times. And so it was with a very different plan in mind that I made my way through this lyrical section of New York’s southern Catskills. I was after a dose of solitude and simplicity, a chance to clear my mind but also to rise to a challenge imposed not by the head-spinning state of the world but by myself. A solo overnight in the woods, something I’d never done before, seemed just the ticket.

I’d expected my wife, who’d been my social-distancing partner every day and night since mid-March, to give the plan a tentative go-ahead. But she embraced it heartily. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one craving alone time.

Fifteen minutes into the hourlong drive, our cell phone service cut out. The paved road leading up the Beaverkill Valley faded to dirt, and we passed the suggestive gates of a Zen monastery. My wife dropped me off at the trailhead, leaving me to set out alone on a flat path along a lake, past campsites that I had decided in advance weren’t remote enough for my purposes. I zipped along, having packed a sleeping bag and not much else. The forecast called for clear weather, and there was at least one lean-to, hiking jargon for a primitive three-walled shelter, along the way.

For a couple miles I climbed alongside a rocky stream, until I reached the head of the beaver meadow where I’d planned to spend the night—only to find the beautifully positioned lean-to there claimed by a pair of beer-drinking guys. I moved on, unsure now of where I’d camp—one more uncertainty in a season that had been full of them.

For a couple miles I climbed alongside a rocky stream, until I reached the head of the beaver meadow where I’d planned to spend the night—only to find the beautifully positioned lean-to there claimed by a pair of beer-drinking guys. I moved on, unsure now of where I’d camp—one more uncertainty in a season that had been full of them.

The terrain went upward again. Cheery little violets and wood sorrels fringed the path, and a pair of rocks were so flat and moss-upholstered that they might as well have been furniture. It would be near dark by the time I reached the next shelter, so I went off-trail and eventually found a clear and level spot amid the ferns. It was nothing special, apart from the appealing possibility that no one had ever camped in this particular patch of woods before.

I inflated my sleeping pad, threw on a fleece, and boiled water for my bag of dehydrated chili, the one edible I’d brought with me. I built a stick fire, not because I needed to but because few things are as naturally absorbing as maintaining a flame. I noted that alder leaves, viewed from below, look like green pinwheels. I listened to the otherworldly metallic fluting of some unseen bird—a sound so remarkable that I had to record it on my phone—against a backdrop of mountain wind. As the sun went down, I tucked myself in.

I’d be lying if I said that I slept soundly. The ground was sloped, the air chilly against my face. The only way to feel comfortable was to bury my head in my sleeping bag. That is, away from the disconcerting reality of my exposure: pitch-black woods all around me and not another soul within shouting distance. For hours I struggled to enter the preferable void of sleep. Eventually, I got there.

Just after 5 a.m., I woke up to find the sun beaming mango-orange light into the forest. Morning! Feeling wobbly from fatigue but exhilarated, I rejoined the trail. I loved the second half of the hike even more: the rhythm of ridge and hollow, the section of dark evergreens, and the complete absence of other hikers. I remembered the quivering unrest I’d felt the night before, when that solitude had been much harder to enjoy. But I also felt proud—and enlarged—for having gone through with it. Recent months had given me an alarming sense of how crowded the planet is; rarely had the relief of stepping away from the herd felt so acute, the hum of the nonhuman world so vivid.

By 9 a.m., I was driving back down to town in the car we’d left for me the day before. I figured I’d done about 8 miles, with exploratory detours included. Over black coffee I told my wife about the little space I’d carved out for myself in a many-thousand-acre wilderness, in a world turned upside down. We both felt better than ever about the decision we’d made some weeks before—to make a permanent move to the Catskills, where we could visit that wilderness whenever we felt like it.

Back at my laptop, the first thing I did was identify the twilight singer as the hermit thrush, which is endowed with the rare gift of a second voice box. In a rundown of Catskills birds, the 19th-century naturalist John Burroughs described the call of this one the sound of “spiritual serenity.” I recommend listening to it on repeat, whether you’re on YouTube or fortunate enough to catch it live.

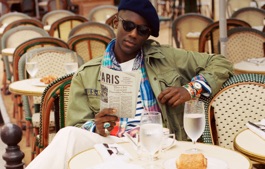

- Photographs by Peter Crosby